Kontrabida [Villain]

Directed by Adolfo Borinaga Alix Jr.

Written by Jerry B. Gracio

After completing work on Kontrabida, Nora Aunor was finally declared National Artist, minus the execrable intrusion of any political leader or showbiz rival (essential disclosure: in June 2014, The FilAm was the first publication to criticize the ill-advised decision by President Benigno Aquino III to drop her name from the list of submissions). What should have been happy news, however, turned out distressing for her followers: she endured a severe medical emergency, declared dead at one point but revived through the intervention of an understandably panicked health team.

Anita as a haughty society matron, in her opening dream sequence. [Screen cap from Kontrabida, courtesy of Magsine Tayo!]

Back to top

11011Kontrabida might therefore be the last opportunity to watch a consummate Aunor film, although the hesitation of casual viewers would be understandable. Its director’s track record has been spotty, and the Metro Manila Film Festival’s consistent rejection of its participation is reminiscent of its judgment on her own auteur project, Greatest Performance, in 1989. Yet what traces remain of GP suggest an ambitious and exemplarily performed work, one of the MMFF’s gravest missteps in a long list of embarrassments. Kontrabida’s an even more egregious instance of insider politicking and institutional negligence.

11011Any initial viewing will instantly distinguish the film as reminiscent of Aunor’s case history during her peak premillennial years, when filmmakers would be able to realize significant achievements by simply having her on board; her skills in streamlining, clarifying, and amplifying character attributes was (and remains) second to none, ascribable to her intensive experience in creative processes and immersion in her compatriots’ sociological concerns. Kontrabida has also turned out to be her first millennial project that references her stature as queer icon, resisting the typical indie practitioner’s tendency to recognize her considerable store of gifts by unnecessarily pedestalizing her.

Jaclyn Jose as Dolly, a devoted fan of Anita. [Screen cap from Kontrabida courtesy of Magsine Tayo!]

Back to top

11011The best way of extracting the film’s potential would be by focusing on the persona that she proffers, inasmuch as Aunor appears in every scene. Early in the plot, her Anita Rosales prepares to dispose of the bric-a-brac she accumulated as a movie supporting player, including her only acting trophy. Any devoted Philippine cinema observer would readily recognize that the object happens to be Anita Linda’s only Maria Clara award, the first institutional prize ever handed out for local film achievement. A fan of hers shows up to purchase it, and it turns out to be played by the recently departed Jaclyn Jose – who professes so much devotion that she decides to return the item to its owner.[1]

11011The parallelisms with film history are profound and moving, yet unobtrusive enough to remain hidden for those who prefer to ignore them. Aunor was the actor who set out to challenge Linda’s First Golden Age stature as the country’s greatest performer and succeeded due to her marshaling of her own privileges as the most successful star in Pinas cinema as well as the upgrade in resources and sensibility of the Second Golden Age; Jose meanwhile carved out her own niche in depicting characters ravaged beyond redemption by poverty and managed to snag the much-coveted Cannes Film Festival best actress prize in the process.

Anita comforts her intellectually challenged neighbor Jai after his father went berserk during his mother and her new partner’s wedding. [Screen cap from Kontrabida courtesy of Magsine Tayo!]

Back to top

11011Linda had been gone by the time Kontrabida was made (her final starring role was also in an Alix film), but neither Aunor nor Jose, just like Linda before them and unlike a long list of their contemporaneous performers, make an effort to recapture their appearance during their Golden Age glory years. The weight they put on, the wrinkles, lumps, and veins on their faces, their slower movements and weaker physical capacities – all affirm their lifetime aspiration to enable their audiences to identify with them. In this instance, they constitute a redefinition of glamour for those who care to ponder on these matters: that it might mean conforming to a near-unattainable youthful ideal for the vast majority, but it could also mean the fulfillment of long-cultivated potential offered for widespread and long-term public consumption: talent, to paraphrase Pauline Kael, will always be a surer guarantee of glamour.

11011Alix of course had collaborated long enough with Aunor to be able to provide unintrusive details that function like humor devices, and then some: Anita begins by slapping someone in her high-camp dream where she plays a society matron, but gets slapped symbolically by her working-class existence in a crisis-ridden administration; she may have retained ownership of her acting trophy, but we eventually get to see how Aunor herself regards these empty symbols of triumph;[2] she lives in a world where those who recognize her adulate her for her past attainments, but she pays the closest attention to people taken for granted by everyone else.

After helping her rehearse for her comeback role, Ramon asks Anita to dance with him. [Screen cap from Kontrabida courtesy of Magsine Tayo!]

Back to top

11011Toward a later part of the film, Alix introduces Bembol Roco, one of her few male contemporaries who has perfectly understood that one must complement Aunor in order to survive a scene with her, in the role of her infirm ex-husband Ramon. The exchanges of scripted lines between them play on their characters’ real-life circumstances and display the warmth and collegiality that their long-time immersion in Philippine film culture has enabled. Anita then forms a pistol with her fingers and aims it at Ramon, then reflexively remarks “bad acting” about herself. The gesture’s payoff is earth-shattering but doesn’t have to be spoiled in a review. Kontrabida nonetheless deserves to be watched for all the tremendous pleasure and pain that the full life of a genuine film artist has brought to the project.

Notes

First published November 18, 2024, as “Nora Returns Minus the Glamour of the Glory Years,” in The FilAm.

[1] Dolly claims that Anita turned her life around by inspiring her to avenge herself on her wrongdoers. In her real-life career, Jaclyn Jose became a much sought-after camp presence in TV drama by specializing in comically snobbish aristocrats, similar to the characters that Anita dreams that she portrays, but directly opposed to Nora Aunor’s actual movie persona.

11011Her first significant interview was titled “Walang Bold sa Langit [Bold Not Allowed in Heaven]” (1986), conducted by Ricky Lee, retitled “May Bold Ba sa Langit? [Is Bold Allowed in Heaven?]” and reprinted in his 2009 anthology Si Tatang at Mga Himala ng Ating Panahon: Koleksyon ng mga Akda or Old Man and the Miracles of Our Time: Collection of Writings, pp. 70-74). In it, Jose mentioned watching Ishmael Bernal’s Himala [Miracle] (1982) for her lesson in acting excellence and described how she wished she could perform on the same level that Nora Aunor had demonstrated, attaining maximal impact via the smallest of gestures. A final Noranian intertext occurs in Emmanuel Dela Cruz’s 2005 film Sarong Banggi [One Night], where Jose’s character, also named Jaclyn, professes fanaticism toward Aunor, her fellow Bicol-born native. (Thanks to Deo Antazo for this vital recollection.)

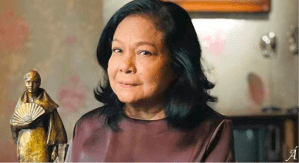

Nora Aunor on the set of Kontrabida, with Anita Linda’s memento. [Photo by Adolfo Borinaga Alix Jr.]

I am indebted to critic-archivist Jojo Devera, not just for providing access to

Kontrabida, but also for pointing out the function that Anita Linda’s Maria Clara trophy signifies in the plot of the film.

Back to top

ORCID ID

ORCID ID

Counteractive

Kontrabida [Villain]

Directed by Adolfo Borinaga Alix Jr.

Written by Jerry B. Gracio

After completing work on Kontrabida, Nora Aunor was finally declared National Artist, minus the execrable intrusion of any political leader or showbiz rival (essential disclosure: in June 2014, The FilAm was the first publication to criticize the ill-advised decision by President Benigno Aquino III to drop her name from the list of submissions). What should have been happy news, however, turned out distressing for her followers: she endured a severe medical emergency, declared dead at one point but revived through the intervention of an understandably panicked health team.

Anita as a haughty society matron, in her opening dream sequence. [Screen cap from Kontrabida, courtesy of Magsine Tayo!]

Back to top

11011Kontrabida might therefore be the last opportunity to watch a consummate Aunor film, although the hesitation of casual viewers would be understandable. Its director’s track record has been spotty, and the Metro Manila Film Festival’s consistent rejection of its participation is reminiscent of its judgment on her own auteur project, Greatest Performance, in 1989. Yet what traces remain of GP suggest an ambitious and exemplarily performed work, one of the MMFF’s gravest missteps in a long list of embarrassments. Kontrabida’s an even more egregious instance of insider politicking and institutional negligence.

11011Any initial viewing will instantly distinguish the film as reminiscent of Aunor’s case history during her peak premillennial years, when filmmakers would be able to realize significant achievements by simply having her on board; her skills in streamlining, clarifying, and amplifying character attributes was (and remains) second to none, ascribable to her intensive experience in creative processes and immersion in her compatriots’ sociological concerns. Kontrabida has also turned out to be her first millennial project that references her stature as queer icon, resisting the typical indie practitioner’s tendency to recognize her considerable store of gifts by unnecessarily pedestalizing her.

Jaclyn Jose as Dolly, a devoted fan of Anita. [Screen cap from Kontrabida courtesy of Magsine Tayo!]

Back to top

11011The best way of extracting the film’s potential would be by focusing on the persona that she proffers, inasmuch as Aunor appears in every scene. Early in the plot, her Anita Rosales prepares to dispose of the bric-a-brac she accumulated as a movie supporting player, including her only acting trophy. Any devoted Philippine cinema observer would readily recognize that the object happens to be Anita Linda’s only Maria Clara award, the first institutional prize ever handed out for local film achievement. A fan of hers shows up to purchase it, and it turns out to be played by the recently departed Jaclyn Jose – who professes so much devotion that she decides to return the item to its owner.[1]

11011The parallelisms with film history are profound and moving, yet unobtrusive enough to remain hidden for those who prefer to ignore them. Aunor was the actor who set out to challenge Linda’s First Golden Age stature as the country’s greatest performer and succeeded due to her marshaling of her own privileges as the most successful star in Pinas cinema as well as the upgrade in resources and sensibility of the Second Golden Age; Jose meanwhile carved out her own niche in depicting characters ravaged beyond redemption by poverty and managed to snag the much-coveted Cannes Film Festival best actress prize in the process.

Anita comforts her intellectually challenged neighbor Jai after his father went berserk during his mother and her new partner’s wedding. [Screen cap from Kontrabida courtesy of Magsine Tayo!]

Back to top

11011Linda had been gone by the time Kontrabida was made (her final starring role was also in an Alix film), but neither Aunor nor Jose, just like Linda before them and unlike a long list of their contemporaneous performers, make an effort to recapture their appearance during their Golden Age glory years. The weight they put on, the wrinkles, lumps, and veins on their faces, their slower movements and weaker physical capacities – all affirm their lifetime aspiration to enable their audiences to identify with them. In this instance, they constitute a redefinition of glamour for those who care to ponder on these matters: that it might mean conforming to a near-unattainable youthful ideal for the vast majority, but it could also mean the fulfillment of long-cultivated potential offered for widespread and long-term public consumption: talent, to paraphrase Pauline Kael, will always be a surer guarantee of glamour.

11011Alix of course had collaborated long enough with Aunor to be able to provide unintrusive details that function like humor devices, and then some: Anita begins by slapping someone in her high-camp dream where she plays a society matron, but gets slapped symbolically by her working-class existence in a crisis-ridden administration; she may have retained ownership of her acting trophy, but we eventually get to see how Aunor herself regards these empty symbols of triumph;[2] she lives in a world where those who recognize her adulate her for her past attainments, but she pays the closest attention to people taken for granted by everyone else.

After helping her rehearse for her comeback role, Ramon asks Anita to dance with him. [Screen cap from Kontrabida courtesy of Magsine Tayo!]

Back to top

11011Toward a later part of the film, Alix introduces Bembol Roco, one of her few male contemporaries who has perfectly understood that one must complement Aunor in order to survive a scene with her, in the role of her infirm ex-husband Ramon. The exchanges of scripted lines between them play on their characters’ real-life circumstances and display the warmth and collegiality that their long-time immersion in Philippine film culture has enabled. Anita then forms a pistol with her fingers and aims it at Ramon, then reflexively remarks “bad acting” about herself. The gesture’s payoff is earth-shattering but doesn’t have to be spoiled in a review. Kontrabida nonetheless deserves to be watched for all the tremendous pleasure and pain that the full life of a genuine film artist has brought to the project.

Notes

First published November 18, 2024, as “Nora Returns Minus the Glamour of the Glory Years,” in The FilAm.

[1] Dolly claims that Anita turned her life around by inspiring her to avenge herself on her wrongdoers. In her real-life career, Jaclyn Jose became a much sought-after camp presence in TV drama by specializing in comically snobbish aristocrats, similar to the characters that Anita dreams that she portrays, but directly opposed to Nora Aunor’s actual movie persona.

11011Her first significant interview was titled “Walang Bold sa Langit [Bold Not Allowed in Heaven]” (1986), conducted by Ricky Lee, retitled “May Bold Ba sa Langit? [Is Bold Allowed in Heaven?]” and reprinted in his 2009 anthology Si Tatang at Mga Himala ng Ating Panahon: Koleksyon ng mga Akda or Old Man and the Miracles of Our Time: Collection of Writings, pp. 70-74). In it, Jose mentioned watching Ishmael Bernal’s Himala [Miracle] (1982) for her lesson in acting excellence and described how she wished she could perform on the same level that Nora Aunor had demonstrated, attaining maximal impact via the smallest of gestures. A final Noranian intertext occurs in Emmanuel Dela Cruz’s 2005 film Sarong Banggi [One Night], where Jose’s character, also named Jaclyn, professes fanaticism toward Aunor, her fellow Bicol-born native. (Thanks to Deo Antazo for this vital recollection.)

Nora Aunor on the set of Kontrabida, with Anita Linda’s memento. [Photo by Adolfo Borinaga Alix Jr.]

Back to top

Share this:

About Joel David