In terms of her health issues, Nora Aunor was only revived once after her vital signs had stopped last year, ironically on the day when she was supposed to find out she’d been finally declared National Artist. This meant that she could attend the awards ceremony under the new President, whom she had endorsed. Typical of her problematic political positions, one of her last statements was an expression of sympathy for the beleaguered former President now imprisoned at The Hague under a warrant served by the International Criminal Court.

11011I won’t deny that I pondered what points to raise in the inevitable obituary once her physical existence gave out, but after a social-media outpouring that still hasn’t abated as of this writing (see FACINE chair Mauro Feria Tumbocon Jr.’s Facebook page, where he has been compiling everything he could find by reposting them), I had to conclude that what she deserves is a series of volumes from authors interested in writing on her, continuing the early volumes in the early 1970s that jump-started the trend in Philippine film-book publishing that continues all the way to the present. A circumstantial, if morbid, discursive opportunity presented itself anyway: her death followed a half-week after Pilita Corrales’s, another long-prevailing talent who also initially gained recognition in singing before branching out to film and television.

The Nora Aunor star at the Eastwood City Walk of Fame. [Megaworld Lifestyle Malls Facebook page]

11011Corrales preceded Aunor’s emergence, which was no surprise considering that the latter was over a decade and a half younger. What will sound incredible is each one’s respective career trajectory: despite Corrales gaining global recognition and immediate local fame, Aunor was the artist whose records sold like proverbial hotcakes, snapped up by fans directly from delivery vans even before they could be inserted and plastic-wrapped in cardboard jackets.[1]

11011Corrales was an engaging, spirited onscreen presence – which makes understandable the major film producers’ hesitation in launching Aunor, who was physically everything that Corrales was not; yet a small independent outfit with ears attuned to box-office performances noted how the movies where Aunor made guest appearances were delivering above-average receipts, which is how Tower Productions devised a string of potboilers and made a killing just by posting her in various romantic locales and getting her to lip-synch the contents of her current long-playing albums.

11011The challenge for scholars of Foucauldian genealogy is to track at what point Aunor decided that phenomenal success was not going to be enough for her, where she aspired not for the expected greater returns on investments, but for artistic peaks that only an exceptional status like hers could facilitate. Perhaps it was when she opted to swing away from cover versions of international hits and standards, toward what we might term the Philippine songbook by classically trained composers as well as the original pop songs that would later segue into what became known as the Manila sound – an innovation where Corrales had actually preceded her.[2] But she knew from her multimedia exposure that there would be no further development possible in this direction, unless she ventured into composition and arrangement herself.

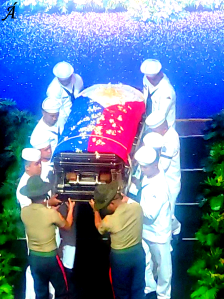

Nora Aunor’s coffin during her wake at Heritage Memorial Park at Fort Bonifacio, Taguig City. [Heritage Park Cemetery Facebook page]

11011Preferring interpretive exertions, she must have deduced that histrionic craft was the obvious next stage. Her own outfit, NV (for Nora Villamayor) Productions, started as early as the year after the declaration of martial law, with now-lost films that were box-office flops because of their art-film qualities. After recovering with a few hit projects, she came up with the tribal epic Banaue (1975), the last film by Gerardo de Leon, and the next year produced a period film, Tatlong Taóng Walang Diyos, her first collaboration with Second Golden Age figure Mario O’Hara. Once more her audience could not catch up with her, but she managed to win the first critics’ performance award, a distinction that may have been precipitate (at least one nominee, Mona Lisa in Insiang, demonstrates superior abilities) but may have been a substitutionary reward for the substantial producer’s risk that she had taken.

11011This led to a short-lived valorization of her stature as a critics’ darling, cut down in 1982 with the group’s inexplicable downgrading of her reading of the lead character in Ishmael Bernal’s Himala, now regarded as one of the possible peaks in Philippine film performance, in contrast with the never-mentioned-since hysterical delivery that the critics selected. (Inside information: I was with the group during this period and made the proper choice, affirmed by the director and writer of both competing films.) As if to demonstrate that their selection was unassailable, the critics continued rejecting her achievements in succeeding years, sometimes against the preferences of all the other award-giving groups, even when the directors of their selected performances complained about their awardees.

11011Aunor of course was more secure in her self-assessment. When the National Artist award was withheld from her twice in succession, she assured everyone that she was disinterested in how the process played out. In case anyone had the impression that she was merely attempting to save face, complaints emerged from film researchers that she did not worry if her collection of prizes was maintained or if certain items were pilfered. Following the principle that dying folks tell no lies, we find her assuring more than one confidant that her source of pride lay in the series of films, whether funded by her outfit or by others, that she was able to see through to completion.[3]

Half-mast state tribute accorded to recipients of the Order of National Artists. [Daily Tribune]

11011Proof that her pride was not misplaced lies in the products themselves. Those familiar with only the standard Aunor canon are missing out on the most impressive single-person display of performing-arts ability in the country’s history. The stage plays she appeared in might now be a permanently unavailable opportunity for millennium-era audiences, but any avid Aunor follower (as I was during her active years) will be able to confirm that, even in trashy or dismissible films, she demonstrated skills beyond anyone else’s reach. The critics who downgraded her deserve to be installed in a hall of shame, but then she wouldn’t have given a hoot about them anyway.

Notes

First published April 18, 2025, as “Nora Aunor: How She Aspired for Artistry,” in The FilAm.

[1] The 1960s through the mid-’70s may be considered the final period of internal labor migration, when job-seekers in the country would move from the rural margins to the urban centers, primarily Manila and suburbs (now Metro Manila); afterward, systemic labor migration would treat Manila as only a way station for overseas work, to be able to compensate for the Marcos dictatorship’s economic mismanagement. Hence the period of emergence of several new stars led by Aunor turned on the presence of working-class Filipinos who had sufficient disposable income to demand a new breed of stars – those who resembled them as closely as possible, instead of the Euro-manqué types foisted on the audience by local producers.

[2] Contrary to conventional belief, her artistic aspiration may have started earlier, when one of her “dismissible” teen musicals, Nora, Mahal Kita (Nora, I Love You, dir. Orlando Nadres, 1972), actually featured original compositions by composer Doming Valdez and lyricist Levi Celerio, later recognized as a National Artist for Music & Literature. Similarly, the major actor-producers who emerged in the wake of the First Golden Age also made sure to invest in “award-worthy” though less commercially successful projects before she came along: Amalia Fuentes (with her AM Productions outfit), Fernando Poe Jr. (FPJ Productions), and Joseph Estrada (Emar, later JE, Productions). What makes Aunor’s record as producer distinctive is that, while at least two of her predecessors (Poe and Dolphy with his RVQ Productions) had longer records of self-produced titles, she had far and away the higher percentage of quality projects. Film critic Mauro Tumbocon observed (via Facebook Messenger chat-group messages) how Poe, Estrada, and Dolphy recognized a kindred spirit in her and never hesitated to provide her with funds or equipment whenever she called on them. A further distinction of her producer’s record, recalled during summations of the career of Ricky Davao (who died not long after she did), was how she also invested in stage material: “In 1982, he made his theater debut in Convent Bread, produced by the late Nora Aunor and directed by Maryo J. de los Reyes” (“Ricky Davao’s Career Through the Years,” Rappler, May 3, 2025).

“Nora Aunor’s State Funeral” from National Flag Days Serye, May 28 – June 12, on Charles Bautista’s Facebook account, posted on May 31, 2025.

[3] I had been privy to some filmmakers’ discussions of projects with Aunor; two first-hand accounts so far include an interview with scriptwriter and her National Artist co-winner for film Ricky Lee, with whom she planned, among other things, a multi-installment autobiographical feature as well as a museum – see Allan Diones’s “Reaksyon ni Sir Ricky Lee sa Pagpanaw ni Ate Guy” [Ricky Lee’s Reaction to Ate Guy’s Death], YouTube, April 18, 2025); as well as Nestor Cuartero’s “Larger than Life, Even in Death,” Manila Bulletin, April 19, 2025, where she volunteers to provide seed money for a welfare fund for film workers. Stories also abound regarding her readiness to distribute her earnings to co-workers, fans, and even strangers whom she perceived as suffering financial deprivation. This perspective contextualizes the only expression of anxiety that she articulated regarding the National Artist Award, to her acting colleague Ruby Ruiz: “Para pag namatay ako, wala nang poproblemahin ang mga maiiwan ko (So that when I’m gone, my heirs won’t have to worry [about money])” – see Jerry Olea’s “Why Ruby Ruiz Declined Offer to Be Nora Aunor’s [Production Assistant],” Philippine Entertainment Portal, April 21, 2025. A final revelation, which she divulged with only her closest circle, was the medical discovery of an advanced stage of cancer, which possibly complicated her health condition although her official cause of death was her long-time heart ailment. I would hesitate speculating on what motives she had and prefer to focus for now on the incomparable legacies that she insisted on enhancing all the way to the end.

First published August 7, 2022, in The FilAm, reprinted in The FilAm: Newsmagazine Serving Filipino Americans in New York 55 (September 2022). The author would like to acknowledge the information and feedback provided by Mauro Feria Tumbocon Jr., Jerrick Josue David (no relation), and Jojo Devera.

First published August 7, 2022, in The FilAm, reprinted in The FilAm: Newsmagazine Serving Filipino Americans in New York 55 (September 2022). The author would like to acknowledge the information and feedback provided by Mauro Feria Tumbocon Jr., Jerrick Josue David (no relation), and Jojo Devera.

ORCID ID

ORCID ID