Faney [Fan]

Directed & written by Adolfo Borinaga Alix Jr.

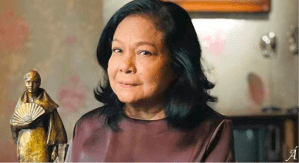

Left: Milagros (Laurice Guillen), hearing the news about Nora Aunor’s death, goes over her collection of Noranian memorabilia. Right: Bea (Althea Ablan), discovering her great-grandmother’s devotion, introduces the word “faney,” contemporary slang for fan. [Faney, Frontrow Entertainment, Intele Builders, Noble Wolf, AQ Films; screen caps by author. Click on pic for clearer images.]

The reverberation of a life after one has died is no longer new because of the dissemination of media-generated popular culture. It should be no surprise that the departure of Nora Aunor has affirmed what film critic and Jefferson public service awardee Mauro Feria Tumbocon Jr. described as “a subgenre yet to be named, where Aunor plays herself as singer-performer” – except that in the recently released

Faney, she no longer exists in our world. The film, part of a substantial list of works already completed (some with her still alive in them), is evidence of how intensively she focused on the legacy she wanted to leave behind: not in terms of trophies or material wealth, but in the record of solid performances that she became known for since her emergence as the country’s most capable actor in the 1970s.

Recovering from the shock of hearing the news, Milagros “remembers” her idol by performing highlights from her favorite Aunor films – left, Bilangin ang Bituin sa Langit (1989, dir. Elwood Perez) and right, Himala (1982, dir. Ishmael Bernal). [Faney, Frontrow Entertainment, Intele Builders, Noble Wolf, AQ Films; screen caps by author. Click on pic for clearer images.]

also testifies to how carefully she cultivated artistic alliances, with Adolfo Alix Jr. taking the place of Mario O’Hara, whose untimely demise from leukemia she mourned openly. Alix was more prolific than O’Hara and already had a few noteworthy projects when he and Aunor first collaborated, but again like O’Hara, his growth trajectory found a grounding that it had been seeking out. Part of the confidence he needed was provided by Aunor herself, since her sheer presence in any type of undertaking always assured, at minimum, an exceptional delivery and a sense that she’d intervened in the project not for highlighting or glamorizing herself, but for enriching the text’s sociopolitical possibilities.

Back to top

Left: Outside the funeral parlor of Aunor’s wake at Heritage Memorial Park, Pacita M. (Roderick Paulate) accosts an interloper whom he recognizes as belonging to a rival camp. Right: After a sabunutan (hair-pulling contest), the rival’s toupee comes off, which Pacita M. then treats it like a washer in sipa (a native footbag-like game). [Faney, Frontrow Entertainment, Intele Builders, Noble Wolf, AQ Films; screen caps by author. Click on pic for clearer images.]

One byproduct of her renewed productivity, after an extended sabbatical in the US, lies in the number of industry participants who had been formerly indifferent, sometimes even hostile, toward her.

Faney features a comic turn by Roderick Paulate in his famed Rhoda persona, playing a devotee who’s accused by another fanatic of betraying a rival star, with whom he erupts in a hair-pulling contest. The character who first mentions the film title is played by Althea Ablan, who’s typically millennial in her adulation of a fictional boy band, while her grandmother is essayed by long-time Aunor associate Gina Alajar, serving as the voice of caution regarding her own mother’s overwhelming, decades-spanning fanaticism.

Left: Wandering on the memorial park grounds, Milagros runs into Edgar (Bembol Roco), with whom she has a wordless, inconclusive confrontation. Right: Ian de Leon, Nora’s biological son, who thanks the mostly elderly fans who showed up at Heritage, is embraced tearfully by Milagros, with Bea realizing that Noranian fandom has been more enduring than her own K-pop fanaticism. [Faney, Frontrow Entertainment, Intele Builders, Noble Wolf, AQ Films; screen caps by author. Click on pic for clearer images.]

The great-grandmother on whom the narrative turns (described as “emotionally wrought yet effective” by film expert Jojo Devera

[1]) is embodied by Laurice Guillen, who springs a few surprises with her presence. She’d trained in theater, as Paulate also did, and where Aunor once immersed in productively: anyone fortunate enough to have seen this trio in their respective stage appearances would instantly understand why theater’s any actor’s true medium. But after several film directors, including the otherwise reliable Lino Brocka, could not maximize her performative potential, she found her own footing when she ventured into film directing. The first jaw-dropper is in how she never had any solo-lead film roles all this time, with

Faney constituting only her third, after Jay Altarejos’s

Guardia de Honor last year and Alix’s

Karera in 2009. The more startling revelation is how perfect she turns out to be for the part, as if all the years of being kept from disclosing her full store of histrionic talent enabled an outpouring of, to use the proper descriptor, Noranian proportions.

Back to top

Left: Informed that the parlor will have to close early for that day, the fans decide to continue waiting outside. Right: After Milagros says that she accepted any actor paired with Aunor, Lola Flor (Perla Bautista) says that she preferred the blockbuster Guy & Pip (Tirso Cruz III) love team most of all and describes how she would stay all day in the movie house and made sure to eat without taking her eyes off the screen. [Faney, Frontrow Entertainment, Intele Builders, Noble Wolf, AQ Films; screen caps by author. Click on pic for clearer images.]

Only favorable results can arise out of such an approach. The film’s few technical imperfections can be overridden by such an all-infusive display of prowess, with several introspective moments held fast by the eloquence of her appearance: where Aunor made her eyes speak volumes, Guillen deploys her entire face – an even more effective mechanism, truth be told. Her penultimate silent moment is when she encounters a male contemporary who we also see for the first time, and no words need to be uttered for us to deduce that he had shared a past with her. This also serves as a throwback to the climax of Aunor with Vilma Santos in Ishmael Bernal’s

Ikaw Ay Akin (1978), which is not the only reflexive moment in the film. In fact the entire outing offers a cornucopia of references for any avid pop-culture follower, starting with the aliases the followers give themselves – “Bona” for Milagros (Guillen’s character) and “Pacita M.” for Paulate’s hell-raising smarty-pants – as well as wisecrack exchanges that sound increasingly familiar until the characters declare the titles of the source films.

Left: Still lighthearted, Pacita M. narrates a low point in his life, when (like many Noranians) he had to work overseas and be unable to see Aunor in person for several years. Right: Milagros returns with her granddaughter Babette (Gina Alajar) and Bea to visit Aunor’s grave at the Heroes Memorial Cemetery. [Faney, Frontrow Entertainment, Intele Builders, Noble Wolf, AQ Films; screen caps by author. Click on pic for clearer images.]

But it’s in the self-owned silent moments where Guillen makes her mark. The first one, when Milagros hears the news of Aunor’s death and brings out her memorabilia collection, sets the tone of melancholy over loss and aging with the comic undercurrent of insistent, undying obsession. The last one, where she stands with her family over Aunor’s grave and gazes in the distance, will reward any open-hearted viewer with an unexpected moment of grace that doesn’t have to be spoiled in a review. Just make sure to allow

Faney to make the mark that Aunor left for us to savor.

Note

First published June 14, 2025, as “Laurice Guillen Is a Devoted Nora Fan in Tribute Film Faney,” in The FilAm.

[1] Devera also provided a later insight, confirmed by the director, to account for how the film was able to make the most of the presence of crowds at Heritage Memorial Park as well as the prevalent air of melancholy that descended on the city: Alix conceptualized and cast the film as soon as the news of Aunor’s death broke out, and took the actors to the relevant locales during the period of her wake.

Back to top

ORCID ID

ORCID ID

Madonna of the Revolution

Lakambini [Noblewoman]

Directed by Arjanmar H. Rebeta

Written by Rody Vera

The biggest still-to-be-resolved controversy about the Philippines’s anticolonial revolution, the first in Asia, centers on the status of Andrés Bonifacio, founder of its liberation army, the Katipunan. Most adequately schooled natives would be aware that recognition of his stature as head of the country’s liberated territories was wrested by a faction that derided his status as uneducated and low-born, despite overwhelming evidence that he’d attained higher levels of historical and political awareness, a result of persistent self-education, than his critics. As a result of duplicitous maneuvering, he and his brother were subjected to a mock trial and summarily executed, their bodies never found despite an arduous month-long search covering two mountains by his widow, Gregoria de Jesús.

11011Also known as Oryang, de Jesus specified Lakambini as her nom de guerre, in acknowledgment of her husband’s position as Lakan or ruler. She accused agents of the usurpation forces of rape and was warned that she could be targeted for assassination. Julio Nakpil, one of her late husband’s lieutenants, married her and kept her safe, enabling her to survive nearly half a century after Bonifacio’s death. A lesser-known fact is that Bonifacio had appointed her his Vice President, which would have made her his successor if the revolution had not been betrayed by Emilio Aguinaldo.

Rocco Nacino & Paulo Avelino (left) as the young Andrés Bonifacio and Julian Nakpil; and Spanky Manikan (right) as the elderly Julian Nakpil. [Screencaps by the author]

Lovie Poe (left) and Elora Españo (right) as the young Gregoria de Jesús. [Screencaps by the author]

Gina Pareño as the elderly Gregoria de Jesús. [Screencap by the author]

11011The only possible hesitation for most audiences, apart from the film’s formal novelty, would be the unremitting sadness of Oryang’s story: not only was she, like the revolution, violated by the very people expected to support her cause, she also lived through all three periods of vicious colonization, dying during World War II before the country attained any form of liberation. She allows herself some consolation in hearing the news of the failure of the fraudulent president’s attempt to legitimize his bloody power-grab via national elections, but issues perhaps the most important historical principle ever made by any Philippine political entity: that history, in its own time, will unmask hidden iniquity (preceding by a few decades Martin Luther King’s much-quoted statement on the arc of the moral universe bending toward justice).

11011Yet the filmmakers involved in the project had been capable in the past of creating difficult reflexive material with light-handed, even comic applications.[1] The daring with which they packaged the narrative of Gregoria de Jesús has not only accurately represented her as a polysemic figure, capable of addressing folks from several generations and persuasions and possibly even nationalities; it has also made her recognizable to millennial audiences, with their preference for experiencing multimedia banter and tolerance for crisscrossing various levels of reality. Lakambini has enabled her to step into the here and now, and the pleasant surprise is that her messages continue to resonate.

Note

Previously published July 27, 2025, in The FilAm. Non-essential disclosures: I was present during the feature film’s first day of shooting, intending to occasionally attend in order to observe a post-celluloid production, since the technological transition to digital occurred while I was busy writing my doctoral dissertation. I was also chair of the board of jurors during the short film festival where Arjanmar H. Rebeta’s entry (see note below) won several prizes. Finally, before production started, I wrote “Theater, Film, & Everything In-Between,” effectively an introduction to Two Women as Specters of History: Lakambini and Indigo Child by Rody Vera (Ateneo de Manila University Press, 2019), the annotated and translated screenplays of two prizewinning films; the book, also a prizewinner, was edited by Ellen Ongkeko-Marfil.

[1] Each of the names who directorially participated had works that may be classified as reflexive but in differing respects: Ellen Ongkeko-Marfil’s last completed film, Indigo Child (2016), was a documentation of a restaged play; Arjanmar H. Rebeta’s previous work, “Libro for Ransom” (2023), was a short film on an investigative journalist’s pursuit of the truth behind the disappearance and recovery of the novels of José Rizal in 1961. Jeffrey Jeturian had two titles, Tuhog (Larger than Life, 2001) and Bikini Open (2005), the first a tracking of the process of the adaptation of a rape case for a commercial film project and the second a mockumentary on a beauty contest.

Back to top

Leave a comment | tags: Commentaries | posted in Film Criticism